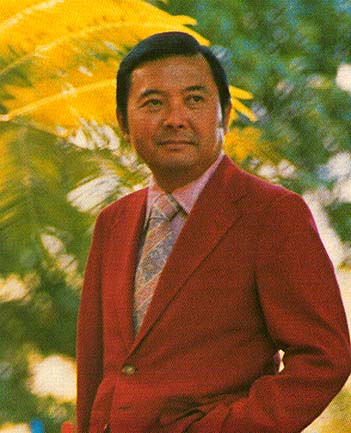

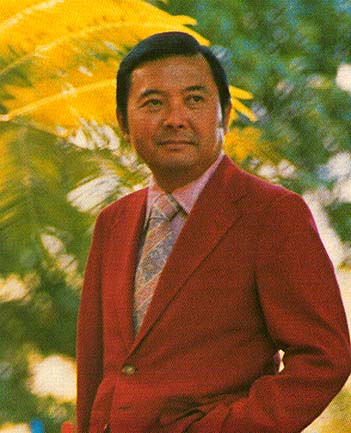

Interview with

Interview with  Interview with

Interview with

February 1997

Sent by mail from Kahuku, HI to Washington D.C.

Written interview by Brooke Barnhill

Senior at Kahuku High

![]()

Q: When and why did you enter the war effort and where were you stationed?

A: Soon after December 7, 1941, all Japanese citizens and non-citizens were designated by the Selective Service System as "4-C." The designation of 4-C meant that I was an "enemy alien." I wanted very much to demonstrate that we were just as good as anyone else, and prepared to defend American's democratic ideals. I wanted to participate in the war effort to preserve our way of life for ourselves and for succeeding generations. I was very anxious to put on a uniform, and be designated as "1-A" -- fit for service by the Selective Service System. In January of 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced, "no loyal citizen of the U.S. should be denied the democratic right to exercise the responsibilities of his citizenship, regardless of his ancestry." With this opportunity I, along with other young Americans of Japanese ancestry, volunteered for the Army. But when the day came for our departure I was in shock. Our names were read in alphabetical order. Inouye was not mentioned. For some reason, I had been turned down by the Army.

During the following days, I learned from the draft board that I had been turned down because my work at the first-aid station was considered essential and because I was enrolled in a premed course at the University of Hawaii. I told the draft board "Give me an hour, then call the aid station and the university. They'll tell you that I've just given my notice to quit by the end of the week." And I did -- two days later, I was ordered to report for induction. I officially joined the Army on March 29, 1943. I was assigned to E. Company, 2nd Battalion and began training at Camp Shelby near Hattiesburg, Mississippi. In May of 1944 we shipped off and landed at Naples, Italy. During my combat service, I was stationed in Europe and fought campaigns in both Italy and France.

![]()

Q: What was your most memorable moment during the war?

A: What I saw on my first day at war was probably one of the most memorable experiences that I will never forget. We landed in Naples, Italy, and were taken through the ruined streets to a temporary shelter area beyond the edge of the city. We had eaten lunch and settled into our tents. Most of the men were anxious to unwind after their long voyage. They were given passes and headed toward Naples. Our new Commanding Officer, Captain Crowley, had assigned me to organize my Company's area. As I was setting up the kitchen and supply tent, I noticed a group of 12 or 15 Italian men and women standing around among the trees in our area. A man from the group who spoke pretty good English approached me and asked if his group could have our leftovers that we had not eaten. The man then called the group over and they began to eat our scraps. I was completely horrified at what I had just witnessed. I thought the man and his group were farmers who wanted to use our leftovers as food for pigs. At the moment, I began to think about who my enemies truly were and how it must have felt to see U.S. troops on their land.

![]()

Q: Would you do it over again?

A: "On" is the very heart of the Japanese culture. "On" requires that, when one man is aided by another, he incurs a debt that is never canceled, one that must be repaid at any opportunity without stint or reservation. "The Inouyes have great 'on' for America," my father said. "It has been good to us. And now it is you who must try to return the goodness of this country. Do not dishonor our name." I have never forgotten my father's words. Our enemy does believe in killing. He has killed millions of blameless people already, and he will kill us if we do not defend ourselves and our liberty. There is no making peace with madmen. You must fight-yes, and kill-to protect the kind of life that helped you grow up to hate killing.

![]()

Q: How did it feel to be the only Japanese regiment in the war?

A: The younger Japanese in the island suffered under special onus. All our lives we thought of ourselves as Americans. Now in this time of national peril, we were seemingly lumped with the enemy by official policy. Despite this, we fought for a place in the war, no matter how menial, and meanwhile struggled to persuade the government to release its anti-nisei rulings. One day in January-little more than a year after the attack on Pearl Harbor-the colonel in charge of the University of Hawaii's ROTC unit (where I was taking a premedical course, planning to become a doctor), called us together. The War Department had just decided to accept 1500 nisei volunteers to join in forming a full fledged combat team. Our draft board, the colonel announced, was ready to take the enlistments. As soon as his words were out, the room exploded with excited shouts. We burst out of there and ran - literally ran - to the draft board, like a bunch of marathoners gone berserk. The scene was repeated all over the islands. Nearly 1000 nisei volunteered on the first day alone. Although our skin was darker than most, we were no less citizens of the United States.

![]()

Q: Did you feel any racism from the other companies?

A: We made up the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and we began our training at Camp Shelby, near Hattiesberg, Miss. I was assigned to E Company, 2nd battalion. Our Commanding Officer was Caucasian and had gone to Roosevelt High School in Honolulu, Captain Ralph B. Ensminger, and from the start there wasn't a man among us who wouldn't have followed him right into General Rommel's command post. There were some Caucasian officers in the early days of the 442nd who sounded off about having to lead "a bunch of Japs" into battle. That would change - we had to show them - but Captain Ensminger was on our side from the first. While in basic training in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, we were informed by Captain Ensminger that we would be treated by the people of Mississippi as "white men."

Public facilities-restaurants, movies, waiting rooms, toilets-were divided into white and colored sections and the South's peculiar concept of democracy took a little getting used to. The first time I saw a Black GI turned away from the YMCA swimming pool, I simply couldn't grasp how an organization that so emphasized its Christian beliefs could exclude a man because he was Black. Yes, there were problems. Once an outfit that had fought the Japanese at Attu came through Camp Shelby and, whether they were honestly confused or just feeling their oats, they threw that hated word "Jap" at us, and accumulated quite a collection of black eyes and fat lips by the time they shipped out. Another time, one of our boys got thrown out of a 69th Division PX and a couple hundred of us marched on the place with blood in our eyes. The MPs had to call up a couple of tanks to turn us back.

![]()

Q: What was the most significant accomplishment of the 442nd?

A: It was while we were in France that a really unexpected thing happened to me. We had been in reserve for a while, but were just about ready to lock horns with the Germans again in what later became famous as the battle to rescue the "The Lost Battalion." The 1st Battalion of the 141st Infantry, part of the almost-all Texan 36th Division, had driven down a ridge east of Biffontaine. Clearing the enemy as it moved forward, the outfit had swept into a narrow valley between Gerardmer and St. Die, and here the Germans, having been rolled back on their own strong support positions, turned to fight. Furthermore, enemy units filtered in behind the unfortunate battalion and completely cut it off from any contact with the American forces. Twice the Texans tried to hammer their way out of the trap, twice they failed. Nearly 1000 GIs had been surrounded and were desperately short of supplies and ammunition. The 442nd was ordered to their relief.

We carried out our mission. However, the cost was great, the 442nd suffered over 300 casualties. The members of the 442nd served our Nation with valor and their achievement helped to dispel in themost dramatic and bloody manner any doubts harbored as to the patriotism of Japanese Americans. The 442nd was the most decorated combat team in U.S. military history. The membership of about 10,000 earned more than 18,000 personal combat decorations, including a Congressional Medal of Honor, 52 Distinguished Service Crosses, 500 Silver Stars, 5,200 Bronze Stars and 9,486 purple hearts. In addition, there were 7 Presidential Unit Citations.

![]()

Q: How has your participation in the War changed your life?

A: When I lost my arm after being struck by an enemy grenade on the battlefield, I knew that I could no longer pursue my dream of becoming an orthopedic surgeon. However, I knew that I still wanted to help people, and work to improve their lives and the lives of their children. I was fascinated by the law and the power it had over our daily lives. From that moment, I decided to become a lawyer and a public servant. After earning a law degree at George Washington University law School, my public service began when I returned to Hawaii to serve with the Deputy Public Prosecutor for the City of Honolulu. In 1954, I was elected to the Territorial Senate. In 1959, I was elected as the first U.S. Congressman from our newly admitted State of Hawaii. In 1962, I was elected to the U.S. Senate, and have served the people of Hawaii, and our nation, proudly and diligently for 35 years.

![]()

Return to the Hawaii Oral History Page

Web page created by Alana Salom, student of The Learning Community