Overcoming the barriers of time and space

|

|

Hiking with the Morans Hiking with the Morans

Jonathan Tourzan

We loaded our supplies onto Steven's Land-Rover. The jeep was quite a sight with

mabati (roofing material) tied on top and the back packed full with food, tents, and

sleeping bags. Steven was going to drive the Land-Rover all the way to the Maasai

settlement on rough, dirt trails.

The matatus picked up our group at the Outward Bound School. They drove us twenty-five

miles over marginal dirt roads to a foot-trail that led to the Maasai settlement. Two

young morans (Maasai warriors) were waiting there for us.

The morans had bright red clay on their heads and generous amounts of beaded jewelry,

ranging from wristbands, to earrings and necklaces. They had come to lead us to their

village and protect us from danger. Because lion attacks were a possibility in the area,

the two warriors carried large spears that they handled astutely. Lions knew better than

to cross the path of a moran because they were no match for these brave warriors. Kimani,

the warden of the Outward Bound School, also accompanied us. Kimani spoke Maa (the

language of the Maasai), Kiswahili, and English so he was a key communication link between

us and the two morans.

The two morans were to escort us to their village. One walked in front of us, and the

other walked behind us as we began our six-and-a-half mile trek across the plains. We were

in a valley between Mt. Kilimanjaro and the Chyulu Hills. The soil was red and dry, and

there were few trees. I noticed small hills located here and there as far as the eye could

see. The day was very hot at first, but, as we neared the village, the sky darkened. When

we were within sight of the village, it started to rain.

Touching

the land Touching

the land

Kelly McJunkin

I felt so close to the Earth as I walked; the great African plains stretched to the

horizon in front of me; the historical Mt. Kilimanjaro rose behind me. The red soil was

soft as I trekked to the Maasai school in my huge boots. Mountains rose to the sky on both

sides of me. I breathed the warm air into my lungs; it had a deep, rich, earthy smell.

Rain began to fall, sprinkling at first, and then pouring. I could feel each cool and

refreshing drop touch my face. After the rain had muddied the topsoil, it stopped. The wet

dirt collected on the bottom of my boots until it was hard to walk with the extra weight.

I saw a small building in the distance; this was our destination, the Elangata-Enkima

Primary School. We finished our fifteen kilometer hike to the village. Barabas, the head

master, and one of his teachers stood outside the old classroom and welcomed us.

Relating

to the morans Relating

to the morans

Julie Paiva

The cool rain felt good after hiking six miles through the bush. The rain stopped as

we approached the Maasai village, but the clouds reminded us that it could soon start

again. When we arrived, some women and the headmaster of the school, Barnabas, greeted us.

Steven McCormick, who had already arrived, instructed us to put up our tents.

When I heard that we were going to be camping in tents, I thought nothing of it. Yet

putting up my green canvas tent next to a mud boma(hut) made me feel a little

uncomfortable. It wasn't long before a group of morans came over to see who we were.

The morans are beautiful people. They are young men between the ages of fourteen and

twenty-five who live in the bush. Traditionally they are warriors or hunters. The morans

drape red and white cloth around themselves, and some wear rubber sandals made out of

tires. They wear an abundance of colorful jewelry, made for them by prospective

girlfriends, and paint their long,

|

|

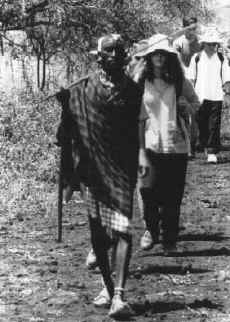

A Maasai moran led us across the Kenyan plains to his village

| We crossed barriers of language, custom, and privilege.

|

twisted hair with thick, red ochre (earth). They are very gentle but can be very

powerful with the spears they carry.

When the morans came over to see our tents, they laughed. I showed them how to get

inside through the zippers and layers of mosquito netting; they seemed intrigued. This was

a wonderful introduction to interacting with the Maasai. Though I could not speak to them

in their language, I spent hours communicating with them. We would just touch one another,

admire each other's hair and clothes, and enjoy being in Maasailand together.

Killing

the goat Killing

the goat

Jonathan Tourzan

To celebrate our arrival in their village, the Maasai had planned a special feast in

which a goat would be killed. I wanted to take part in all the Maasai festivities, but,

being a vegetarian, I felt I could only eat the meat if I had a hand in killing the

animal. Every time an individual eats meat, they are causing suffering to some living

being. Because most people do not kill the animals that they eat, they are out of touch

with this reality. If I were going to eat meat, I did not want to avoid witnessing the

suffering experienced by the animal. In fact, I wanted to cause its suffering with my own

hands. I asked Musa (Moses), a Maasai elder, if it would be all right for me to kill the

goat. Musa appreciated my desire to be involved, and he readily agreed.

Musa took me into a dark schoolroom. I saw the goat in the corner with a rope around

its neck. Barnabas, the schoolmaster, held the animal tightly. Musa gave me a knife; I was

scared. I kept asking whether it was time to start. Musa and Barnabas put tree branches

and metal sheets on the ground to keep blood off the dirt floor. They also put a pot on

the metal sheets to capture the blood from the goat's neck; the Maasai consider blood a

delicacy and enjoy drinking it. Musa told me that it was time to start.

As I cut the goat's throat, its body writhed. I tried to kill with compassion,

experiencing the suffering of the goat, letting its pain enter my heart. When I reached

the artery at the back of the goat's neck, I felt the life start to leave its body. After

Musa cracked its neck, its body went limp, and the goat died. Everything got so quiet in

the room. I felt as if the goat were still there, still alive.

At this point, we began to butcher its warm body. I held one leg, and Musa pulled off

the skin. After the skinning, we separated the organs. The Maasai use every part of the

animal. Musa removed the raw kidney from the goat. He cut it into four slices and gave

pieces to Ryan, Andy, Gary, and me. The kidney was still warm from the kill. I had not

eaten meat for almost a year. Shortly after eating the kidney, I left the room.

As I walked to the stream to wash my hands, I thought about what I had just done. I

felt like I understood the process of dying in a deeper way. I also felt a great respect

for all life. Plants and animals are all alive and must be killed to be eaten. Killing a

goat made me conscious of this fact. I am now much more grateful for all the food I

receive. The experience also confirmed my vegetarian beliefs, as taking the life of an

animal is not a pleasant experience. As I washed my hands in the stream, I prayed for the

goat. I offered it my love to give it the strength for its next incarnation.

|