Celebrating life's wonderful gifts

|

|

Sharing gifts of love Sharing gifts of love

Leah Mowery

I sat on a rock in front of my tent in Maasai land. The sky was gray and cloudy, and

the air was hot and wet from the rain that fell throughout the day. The land stretched out

in all directions, with only small hills to upset the plain. I wore my kanga, a

wrap-around skirt worn in Kenya, and hiking boots borrowed from the Outward Bound school.

I felt clunky and immobile; I even felt awkward crossing my legs.

I had a string bracelet attached to my kanga by a safety pin. We heard that the Maasai

were going to be giving us jewelry as presents. This motivated Ian and a few of us to

weave friendship bracelets to give in return.

People were standing around me, and two Maasai morans were communicating in Kiswahili.

As I worked on the bracelet, I thought about how I used to make them with my friends;

here I was with the Maasai, making these same bracelets. A few Maasai would even be

wearing them, just as some of my friends did.

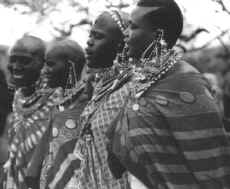

During the baraza (party), we were standing in a circle of about 350 Maasai. Everyone from

the surrounding bomas had come to see us and to welcome us. A mama entered the circle with

a basket of jewelry. She would select an appropriate piece and put it on one of us,

sometimes with the help of another mama. Musa explained to us the significance of each

colorful piece of jewelry. I received an oval earring that was half a foot long. It was

made out of leather and beaded on the front. It was too big for my ear, so they put it on

a beaded string for me to wear around my neck.

I wanted to pass the jewelry that I had made on to someone, so I went to Musa and

asked him to whom I should give it. He led me to the side of the circle where more women

sat and spoke to them in Maasai. Then he lifted one woman's arm and told me that I could

give it to her. As I tied the green and blue bracelet onto her wrist, my hands were

shaking; I feared that I wouldn't be able to get the knot tied. I didn't know what she

thought of the present. She made some comment to her companions, but I couldn't understand

what it was. She had been smiling the whole time, but I was not sure if she enjoyed it.

I didn't know to whom I should give the other bracelet. I didn't know any of the

women, and Musa had left me long ago and was with other members of my class. I looked at

the women and got smiles in return, but nothing led me to a particular person.

I saw Susan near me talking to an old mama. I asked her if she had any ideas about

giving the other bracelet. Susan looked down at the old woman with love and respect. Susan

said, “If I were to tell you who I thought should get it, it would have to be this

mama. She is a special woman.”

I followed her advice, and, as I was tying it on, I felt like I was paying a

compliment to a very important person. I got the feeling that this woman was respected by

her community and that she was a woman of great knowledge. I felt honored knowing that she

would wear something that I had made. I hoped that she would remember me and this day with

love and treat the present with care.

Exchanging

gratitude Exchanging

gratitude

Jenelle Flaherty

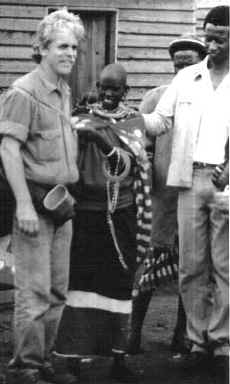

I was standing at the edge of a circle of 350 happy, colorful Maasais with members of

our group spread throughout. Gary was at the center presenting gifts on our group's behalf

to the senior elders of the tribe. We gave them trees for shade, mabati for their school,

and a five hundred dollar gift toward the construction of a new classroom.

Musa, the Maasai who had arranged our visit, translated the elder's thankful words

into English for us. Jon, Fiona, Laura, and Kelly carried the mabati into the circle on

their shoulders. A group of elders sitting close to Rebecca and me clapped to show their

thanks.

One of them turned to Rebecca and looked at her with deep gratitude and respect; he

then spit on the ground in front of her, and turned back to the center of the circle to

enjoy the rest of the ceremonies.

Rebecca and I stood there confused, wondering what the elder meant by spitting in

front of her. Later I talked with Steven McCormick about it. He explained to me that some

Kenyans, especially Maasai, have a custom of spitting at one's feet to show their

gratitude. I felt good knowing that the Maasai people respected and appreciated our gifts,

although I still felt strange about the spitting.

Jumping

with the morans Jumping

with the morans

Jonathan Tourzan

The young warriors were doing a traditional dance with jumping and chanting to

celebrate the baraza.

|

|

Barnabas presents Gary a gift of tribal elder beads

| Gifts transcended the physical, they became gifts of the heart.

|

This same dance gives the warriors the courage necessary to kill a lion, part of the

Maasai rite of passage into manhood. After initiation, the morans continue to do the dance

on festive occasions. Our visit and the resulting baraza created such an occasion, and a

dozen morans gathered to sing and dance for us.

Musa approached Andy and me. He offered us the opportunity to join in; then he gave us

ceremonial sticks. All the warriors carry smooth sticks as signs of power. We joined the

circle and began chanting. The warriors were singing and moving their heads up and down to

the pulsing rhythm. They encouraged me with friendly laughter and looks of approval.

Each dancer took turns going into the middle of the circle and jumping. When my turn

came, I was a little nervous. As I stepped into the circle, my bashfulness disappeared.

Three times I jumped into the air. My mind felt as vast as the sky. After my final jump, I

thumped my feet onto the ground and returned to the circle.

Leaning against my fellow dancers, I felt like a Maasai warrior. I knew how fortunate I

was to receive this opportunity to participate directly in their traditional culture.

Understanding

morans Understanding

morans

Leah Mowery

The tent encloses me in hot, sticky air, so I unzip the tent and get out. In front of

me are three Maasai men, standing and talking together in their native tongue.

They have a unique shape to their bodies, as if the wind on the plains and the harsh

conditions of the sun shaped their bones. Their bodies are strong from the intense work

that nomadic life demands; they seem to stretch toward the sky. Crimson cloth drapes over

their shoulders and hangs below their waist. This covers their torso much like a robe. The

men lean on walking sticks that appear to become extensions of their bodies. They walk

with pride and dignity. Their steps connect with the land in a most spiritual way. The red

ochre clay in their hair connects them even more to the land on which they live in such

harmony.

Behind them, the peaks of Mt. Kilimanjaro rise out of an expanse of land that seems to

go on forever. Around it are gray clouds, clouds quite different from those at home. They

are strong and sharply defined. I imagine what it would be like to live with such beauty

every day. I imagine this beauty surrounding the Maasai's unconscious spirit, dripping in

and making them whole. Unlike so many people in my community that are detached from their

environment, the morans live in close relation to everything around them. They know how to

work with the world around them.

Realizing

our objectives Realizing

our objectives

Gary Bacon

After the celebration, we took down our tents andpacked our gear. We hiked in the

direction of our vehicles, only to find them stuck in the mud. We alternated riding,

disembarking, and pushing the matatus out of the mud through the late afternoon and

evening.

It was dark by the time we arrived at our destination at the Outward Bound Mountain

School in Loitokitok. We were tired from our exciting adventure into the Maasailand, and

wet and muddy from our arduous adventure back out. Everyone had helped and worked together

that last day; no one had complained about the mud and rain. We had attained a heightened

sense of unity; our group had matured and was functioning as one.

We went to bed tired, yet we knew that our objectives for this trip had been met. Soon

we would be headed back home to the United States.

|